Humanity is the product of the same processes as all other species that have dwelt on Earth, with our well-being inextricably tied to the health of the biosphere. Contemporary science has confirmed nature’s myriad links, but as early as 1911 John Muir poetically expressed ecology’s central insight. “When we try to pick out anything by itself,” Muir wrote in My First Summer in the Sierra, “we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” The twin ideas of evolutionary kinship and ecological connectivity are profoundly disruptive to the delusion of human exceptionalism, that somehow the rules don’t apply to us, that our cleverness is boundless, even to the point of transcending biological limits. One hundred years after his death, John Muir’s legacy could not be more vital. Inspired by the love he felt for the wild world, today’s vision for the future of conservation—and the future of the Earth—is one of planetary rewilding, where a scaled-back human civilization is embedded in a matrix of wildness, and where at least half of the globe is left to nature. It is a vision both idealistic and achievable: Broad swaths of green and blue— beautiful, untrammeled, evolution-supporting lands and waters encircling the Earth, where wild life and people flourish together.

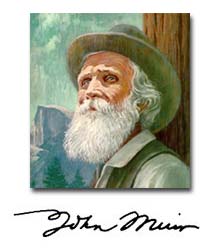

John Muir (April 21, 1838 – December 24, 1914) was a Scottish-American naturalist, author, and early advocate of preservation of wilderness in the United States. His letters, essays, and books telling of his adventures in nature, especially in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California, have been read by millions. His activism helped to preserve the Yosemite Valley, Sequoia National Park and other wilderness areas. The Sierra Club, which he founded, is a prominent American conservation organization. The 211-mile (340 km) John Muir Trail, a hiking trail in the Sierra Nevada, was named in his honor.

Sources:

Tom Butler and Eileen Crist. John Muir’s Last Stand

Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Muir

- Log in to post comments