A year and a half ago, with symposia and reverential speeches, the United States and much of the world marked the 50th anniversary of Rachel Carson's book "Silent Spring" and her courageous warnings about environmental threats. Monday -- the 50th anniversary of Carson's death -- is an opportune time to admire her equally courageous silence about matters that could have blunted the book's impact. Most people are surprised to learn that Carson lived only about 18 months after the publication of "Silent Spring." On April 14, 1964, a month shy of her 57th birthday, Carson died in the Maryland suburb of Silver Spring of complications of metastasizing breast cancer. Sadly, she had become a polarizing figure in an increasingly vituperative political atmosphere. Carson did not live to see the positive impact of her message -- prohibition of the agrichemicals aldrin, dieldrin and heptachlor; passage of the National Environmental Policy Act; establishment of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; the banning of DDT in the United States in 1972 and the end of its use by much of the world's agriculture within the half-century.

Nor did Carson live long enough to accept the Presidential Medal of Freedom (Jimmy Carter awarded it to her posthumously in 1980) or to be present in 2008 when the post office in her hometown of Springdale was named in her honor. She never celebrated the first Earth Day or rejoiced in the rise of environmental consciousness worldwide that her work inspired.

But Carson did live long enough to witness the positive impact of her work in three important public events.

First, she appeared with quiet confidence on the acclaimed TV documentary "CBS Reports," the forerunner of "60 Minutes," in April 1963. Although many in the petrochemical industry and medical establishment rudely demanded Carson's "silence," her appearance reached millions of people who may not have read her book but were convinced by her evidence that pesticides were being misused. Many also were appalled by the ignorance of government officials who were interviewed on the show.

Second, she lived long enough to be vindicated by the President's Science Advisory Committee's report on "Use of Pesticides." The report, released May 15, 1963, affirmed her allegations and concluded with astonishing candor that until the publication of "Silent Spring," the American public did not know that pesticides were toxic.

Finally, in early June, despite increasingly serious angina attacks, she testified before two Senate subcommittees on the interdependence of the human and natural worlds and the dangers that unregulated pesticide use posed to both.

The public was shocked by the news of Carson's death on that warm spring evening 10 months later. Only a few people had known about the desperate state of her health. Jay McMullen, the producer of the "CBS Reports" segment, suspected she was ill when he interviewed her in Maine in September 1962. Two months later, when he and Eric Sevareid, the distinguished host of the show, finished filming at Carson's home in Silver Spring, Sevareid expressed shock at how ill Carson appeared. He urged McMullen to finish the program quickly, telling him, "You've got a dead leading lady."

Between the publication of "Silent Spring" and her death, Carson purposely deflected speculation about her health.

In June 1963, when Carson appeared before California Sen. Abraham Ribicoff's subcommittee investigating pesticides and other pollutants, she spoke energetically and eloquently for 40 minutes. Few of the mostly male participants noticed that she wore an ill-fitting dark wig and used a cane. After that, Carson rarely appeared in public. Most of her friends, even some of her closest ones in Maryland, simply never knew she had been battling cancer for much of the nearly five years it had taken to research and write "Silent Spring."

Why did Rachel Carson so deliberately cut herself off from the support of caring friends? The answer lies only partly in her desire for privacy and her determination to let nothing stand in the way of finishing her book or defending its conclusions.

She admitted to some friends that she had endured a "catalog of illnesses" while writing the book. Iritis had impaired her vision, and there were weeks when she could not see to read or write. She had undergone a radical mastectomy in 1960 but had no further treatments. A year later, however, it was clear the cancer had spread. As she wrote to a friend, "I suppose it's a futile effort to keep one's private affairs private. Somehow I have no wish to read of my ailments in the gossip columns. Too much comfort for the chemical companies."

She tried gold treatments for her arthritis and biweekly radiation for the cancer. She rejected chemotherapy because she knew it would make her too weak to continue writing or to defend the book, assuming she even was able to finish it. Desperate to keep going, she submitted to experimental surgery at the Mayo Clinic.

But another equally compelling reason for her silence was political, not personal. The chemical companies and the pesticide industry trade group, the National Agricultural Chemicals Association, spent well over a quarter of a million dollars to try to persuade the public that Rachel Carson was merely an alarmist. Had they learned of her cancer, they would have used it to undermine her science and question her motives and objectivity. Had her cancer been made public, critics would have said her environmental charges were simply the warped ideas of a dying woman. Financially vulnerable, she also kept silent to protect the welfare of her mother and a young nephew she had adopted.

Carson also kept quiet about other matters. She wanted to support several controversial causes that she cared about passionately. I consider these her "subversive" activities because had her support been made public, she would have risked even crueler characterizations than that of a "nun of nature," a sentimental "woman who loved cats," or a "spinster" overwrought about genetics, as critics all had labeled her. A supporter of such "fringe" groups could not be taken seriously as a scientist whose conclusions might influence government policy.

As a longtime member of the Animal Welfare Institute, Carson quietly supported the bill that became the basis for the Laboratory Animal Welfare Act of 1966. In letters to congressmen, she also strongly opposed the use of the steel-jaw leg-hold traps and the poisoning of wildlife, particularly wolves and coyotes. She agreed to serve on the board of the Defenders of Wildlife and wrote the foreword to Ruth Harrison's scathing book "Animal Machines," in which the British activist exposed the mistreatment of caged farm animals. Any of these activities, if aired publicly, would have opened her to charges of unscientific emotionalism and sentimentalism or worse.

Most "subversive" of all, Carson supported Jerome Rodale and the farm movement that promoted the benefits of organically grown food. As an expert on the dangers of pesticides in agriculture, she saw the potential public health benefits of organic food. But in the early 1960s, organic farming was considered by many as "quackery." Had Carson's support been known to the chemical lobby, it would have further jeopardized her claims in "Silent Spring."

In 1963, attacks on Carson became increasingly personal and vituperative as the chemical industry and big agriculture were put on the defensive. In one of her last speeches, Carson observed, "In spite of the truly marvelous inventiveness of the human brain, we are beginning to wonder whether our power to change the face of nature should not have been tempered with wisdom for our own good, and with a greater sense of responsibility for the welfare of generations to come." These are not the words of a revolutionary, but the thoughtful, prophetic words of someone who cared passionately for the preservation of the Earth and all its creatures.

When Sen. Ribicoff learned of Rachel Carson's death, he spoke for many Americans in telling reporters, "Today we mourn a great lady. All mankind is in her debt." Half a century later, I'd edit his eulogy to add that if future springs are not silent but alive with the twittering of birds and the buzzing of bees, and if today we have a keener appreciation of the importance of preserving the wonder of nature for ourselves and our children's children, then all of creation is in her debt.

■ ■ ■ ■ ■

Source: Linda Lear in the Pittsburgh Post Gazette, 13 April 2014

http://www.post-gazette.com/opinion/Op-Ed/2014/04/13/THE-NEXT-PAGE-Rach…

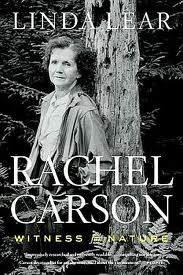

Bethesda, Md., resident and Winchester Thurston School graduate Linda Lear (linda@lindalear.com) is the author of "Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature." Her donation of Carson materials and other historic items created the Linda Lear Center for Special Collections and Archives at Connecticut College. She has a doctorate in U.S. political history from George Washington University.

Read more: http://www.post-gazette.com/opinion/Op-Ed/2014/04/13/THE-NEXT-PAGE-Rach…

- Log in to post comments