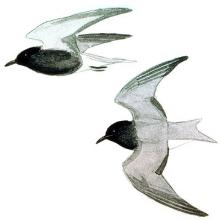

Trauerspiel um Trauerseeschwalbe - Nur zwölf Küken der bedrohten Art wurden in diesem Jahr auf Eiderstedt flügge

Es werden einfach nicht mehr Trauerseeschwalben (Chlidonias niger) auf Eiderstedt, auch nicht im EU-Vogelschutzgebiet. In diesem Jahr zählte Experte Claus Ivens 20 Brutpaare und zwölf flügge Küken, im vergangenen Jahr waren es 21 Paare und 21 Küken. Damit setzt sich der Negativ-Trend fort. So waren es 2003 noch 58 Brutpaare und 103 flügge Küken. Einen großen Einbruch verzeichnete Ivens 2009: 36 Paare zogen acht Jungvögel auf. 2008 waren es noch 51 Paare, allerdings wurden nur zwei Küken flügge. Der ehemalige Landwirt aus Kotzenbüll ist seit seiner Jugend fasziniert von dem zierlichen Vogel und kümmert sich seit Jahrzehnten um den Schutz dieser vom Aussterben bedrohten Art, die auf künstlichen Nistflößen auf Tränkekuhlen in den Weiden der Halbinsel brütet. Die legen Ivens und ein Team des Naturschutzbunds Kiel in jedem Frühjahr aus. 121 sind es im EU-Vogelschutzgebiet, 29 im Oldensworter Vorland.