Greenpeace: Europe's dependency on chemical pesticides is nothing short of an addiction

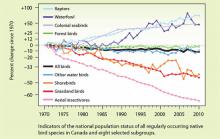

Industrial agriculture, with its heavy use of chemical pesticides, pollutes our water and soil and leads to loss of habitats and biodiversity, according to a Greenpeace report. With almost one in four (24.5%) vulnerable or endangered species in the EU being threatened by agricultural effluents, including the use of pesticides and fertilizers, species survival and crucial ecosystem services, like pollination, are at risk. Political and financial support is urgently needed to shift from chemical-intensive, damaging agricultural methods, to sustainable ecological farming practices. In Europe, a catastrophic decline of insects was signaled by the "IUCN Task Force on Systemic Pesticides" in 2015, after analyzing over 800 scientific reports. The impacts can be devastating, as 70 per cent of the 124 major commodity crops directly used for human consumption like apples and rapeseed are dependent on pollination for enhanced seed, fruit, or vegetable production. Dirk Zimmermann, Ecological Farming Campaigner at Greenpeace Germany said: "Europe's dependency on chemical pesticides is nothing short of an addiction. Crops are routinely doused with a variety of chemicals, usually applied multiple times to single crops throughout the whole growing season. Non-chemical alternatives to pest management are already available to farmers but need the necessary political and financial support to go mainstream."