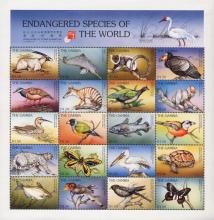

No Fish, No Fowl: European Fish and Birds in Decline

Two new reports on Europe’s endangered fish and bird species were released this week by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The first report is itself a milestone: the first full assessment of all of Europe’s 1,220 marine fish species. The study found that 7.5 percent of those species were threatened with extinction. Worst hit, as we’ve seen before, were sharks, rays and chimaeras. A full 40.4 percent of those European species (known collectively as chondrichthians) face the threat of extinction and nearly that many have declining populations. The second report looked at all 533 bird species that spend at least part of their time in Europe and found that 13 percent are threatened. Four species have been declared regionally extinct in Europe. Others, such as the sociable lapwing (Vanellus gregarius), aren’t far behind. Another 28 species have been assessed as endangered or critically endangered on the continent. Most of these are also at risk through the remainder of their ranges.