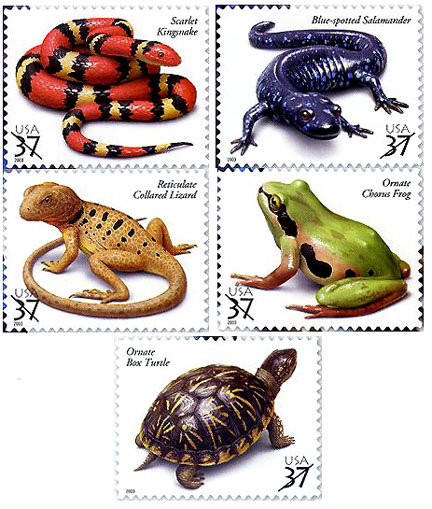

The first-ever estimate of how fast frogs, toads and salamanders in the United States are disappearing from their habitats reveals they are vanishing at an alarming and rapid rate. According to the study released today in the scientific journal PLOS ONE, even the species of amphibians presumed to be relatively stable and widespread are declining. And these declines are occurring in amphibian populations everywhere, from the swamps in Louisiana and Florida to the high mountains of the Sierras and the Rockies. The study by USGS scientists and collaborators concluded that U.S. amphibian declines may be more widespread and severe than previously realized, and that significant declines are notably occurring even in protected national parks and wildlife refuges." Amphibians have been a constant presence in our planet's ponds, streams, lakes and rivers for 350 million years or so, surviving countless changes that caused many other groups of animals to go extinct," said USGS Director Suzette Kimball. "This is why the findings of this study are so noteworthy; they demonstrate that the pressures amphibians now face exceed the ability of many of these survivors to cope." On average, populations of all amphibians examined vanished from habitats at a rate of 3.7 percent each year. If the rate observed is representative and remains unchanged, these species would disappear from half of the habitats they currently occupy in about 20 years.

The more threatened species, considered "Red-Listed" in an assessment by the global organization International Union for Conservation of Nature, disappeared from their studied habitats at a rate of 11.6 percent each year. If the rate observed is representative and remains unchanged, these Red-Listed species would disappear from half of the habitats they currently occupy in about six years.

"Even though these declines seem small on the surface, they are not," said USGS ecologist Michael Adams, the lead author of the study. "Small numbers build up to dramatic declines with time. We knew there was a big problem with amphibians, but these numbers are both surprising and of significant concern."

For nine years, researchers looked at the rate of change in the number of ponds, lakes and other habitat features that amphibians occupied. In lay terms, this means that scientists documented how fast clusters of amphibians are disappearing across the landscape.

In all, scientists analyzed nine years of data from 34 sites spanning 48 species. The analysis did not evaluate causes of declines.

The research was done under the auspices of the USGS Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative, which studies amphibian trends and causes of decline. This unique program, known as ARMI, conducts research to address local information needs in a way that can be compared across studies to provide analyses of regional and national trends.

Brian Gratwicke, amphibian conservation biologist with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, said, "This is the culmination of an incredible sampling effort and cutting-edge analysis pioneered by the USGS, but it is very bad news for amphibians. Now, more than ever, we need to confront amphibian declines in the U.S. and take actions to conserve our incredible frog and salamander biodiversity."

The study offered other surprising insights. For example, declines occurred even in lands managed for conservation of natural resources, such as national parks and national wildlife refuges.

"The declines of amphibians in these protected areas are particularly worrisome because they suggest that some stressors – such as diseases, contaminants and drought – transcend landscapes," Adams said. "The fact that amphibian declines are occurring in our most protected areas adds weight to the hypothesis that this is a global phenomenon with implications for managers of all kinds of landscapes, even protected ones."

Amphibians seem to be experiencing the worst declines documented among vertebrates, but all major groups of animals associated with freshwater are having problems, according to Adams. While habitat loss is a factor in some areas, other research suggests that things like disease, invasive species, contaminants and perhaps other unknown factors are related to declines in protected areas.

"This study," said Adams, "gives us a point of reference that will enable us to track what's happening in a way that wasn’t possible before."

The publication, Trends in amphibian occupancy in the United States, is authored by Adams, M.J., Miller, D.A., Muths, E., Corn, P.S., Campbell Grant, E.H., Bailey, L., Fellers, G.M., Fisher, R.N., Sadinski, W.J., Waddle, H., and Walls, S.C., and is available to the public.

Read a USGS blog, Front-row seats to climate change, about 3 other recent USGS amphibian studies. For more information about USGS amphibian research, visit http://armi.usgs.gov/

Source: USGS Newsroom, 5/22/2013

http://www.usgs.gov/newsroom/article.asp?ID=3597#.VTI2ciHtmko

- Login om te reageren