Imidacloprid is one of the most commonly used insecticides in agricultural practice, and its application poses a potential risk for soil microorganisms. The objective of this study was to assess whether changes in the structure of the soil microbial community after imidacloprid application at the field rate (FR, 1 mg/kg soil) and 10 times the FR (10 × FR, 10 mg/kg soil) may also have an impact on biochemical and microbial soil functioning. The obtained data showed a negative effect by imidacloprid applied at the FR dosage for substrate-induced respiration (SIR), the number of total bacteria, dehydrogenase (DHA), both phosphatases (PHOS-H and PHOS-OH), and urease (URE) at the beginning of the experiment. In 10 × FR treated soil, decreased activity of SIR, DHA, PHOS-OH and PHOS-H was observed over the experimental period. Nitrifying and N2-fixing bacteria were the most sensitive to imidacloprid. The concentration of NO3− decreased in both imidacloprid-treated soils, whereas the concentration of NH4+ in soil with 10 × FR was higher than in the control. Analysis of the bacterial growth strategy revealed that imidacloprid affected the r- or K-type bacterial classes as indicated also by the decreased eco-physiological (EP) index. Imidacloprid affected the physiological state of culturable bacteria and caused a reduction in the rate of colony formation as well as a prolonged time for growth. Principal component analysis showed that imidacloprid application significantly shifted the measured parameters, and the application of imidacloprid may pose a potential risk to the biochemical and microbial activity of soils.

Source:

Mariusz Cycoń & Zofia Piotrowska-Seget. Biochemical and microbial soil functioning after application of the insecticide imidacloprid. Journal of Environmental Sciences. Available online 11 November 2014. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2014.05.034

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1001074214002010

- Log in to post comments

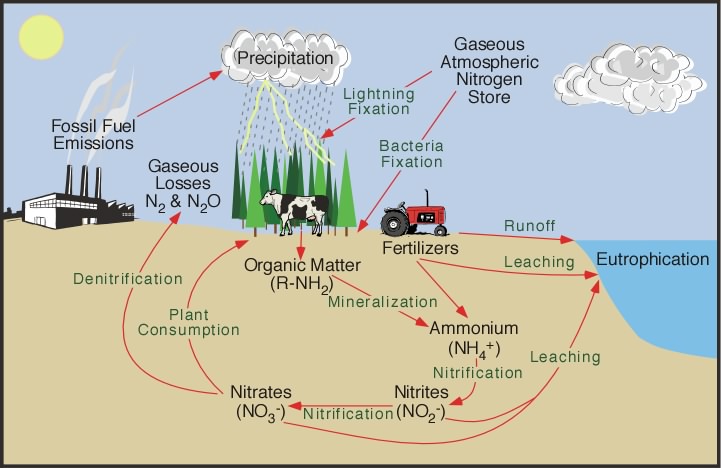

The nitrogen cycle

The nitrogen cycle represents one of the most important nutrient cycles found in terrestrial ecosystems. Nitrogen is used by living organisms to produce a number of complex organic molecules like amino acids, proteins, and nucleic acids. The store of nitrogen found in the atmosphere, where it exists as a gas (mainly N2), plays an important role for life. This store is about one million times larger than the total nitrogen contained in living organisms. Other major stores of nitrogen include organic matter in soil and the oceans. Despite its abundance in the atmosphere, nitrogen is often the most limiting nutrient for plant growth. This problem occurs because most plants can only take up nitrogen in two solid forms: ammonium ion (NH4+ ) and the ion nitrate (NO3- ). Most plants obtain the nitrogen they need as inorganic nitrate from the soil solution. Ammonium is used less by plants for uptake because in large concentrations it is extremely toxic. Animals receive the required nitrogen they need for metabolism, growth, and reproduction by the consumption of living or dead organic matter containing molecules composed partially of nitrogen.

In most ecosystems nitrogen is primarily stored in living and dead organic matter. This organic nitrogen is converted into inorganic forms when it re-enters the biogeochemical cycle via decomposition. Decomposers, found in the upper soil layer, chemically modify the nitrogen found in organic matter from ammonia (NH3 ) to ammonium salts (NH4+ ). This process is known as mineralization and it is carried out by a variety of bacteria, actinomycetes, and fungi.

Nitrogen in the form of ammonium can be absorbed onto the surfaces of clay particles in the soil. The ion of ammonium has a positive molecular charge is normally held by soil colloids. This process is sometimes called micelle fixation. Ammonium is released from the colloids by way of cation exchange. When released, most of the ammonium is often chemically altered by a specific type of autotrophic bacteria (bacteria that belong to the genus Nitrosomonas) into nitrite (NO2- ). Further modification by another type of bacteria (belonging to the genus Nitrobacter) converts the nitrite to nitrate (NO3- ). Both of these processes involve chemical oxidation and are known as nitrification. However, nitrate is very soluble and it is easily lost from the soil system by leaching. Some of this leached nitrate flows through the hydrologic system until it reaches the oceans where it can be returned to the atmosphere by denitrification. Denitrification is also common in anaerobic soils and is carried out by heterotrophic bacteria. The process of denitrification involves the metabolic reduction of nitrate (NO3- ) into nitrogen (N2) or nitrous oxide (N2O) gas. Both of these gases then diffuse into the atmosphere.

Almost all of the nitrogen found in any terrestrial ecosystem originally came from the atmosphere. Significant amounts enter the soil in rainfall or through the effects of lightning. The majority, however, is biochemically fixed within the soil by specialized micro-organisms like bacteria, actinomycetes, and cyanobacteria. Members of the bean family (legumes) and some other kinds of plants form mutualistic symbiotic relationships with nitrogen fixing bacteria. In exchange for some nitrogen, the bacteria receive from the plants carbohydrates and special structures (nodules) in roots where they can exist in a moist environment. Scientists estimate that biological fixation globally adds approximately 140 million metric tons of nitrogen to ecosystems every year.

The activities of humans have severely altered the nitrogen cycle. Some of the major processes involved in this alteration include:

The application of nitrogen fertilizers to crops has caused increased rates of denitrification and leaching of nitrate into groundwater. The additional nitrogen entering the groundwater system eventually flows into streams, rivers, lakes, and estuaries. In these systems, the added nitrogen can lead to eutrophication.

Increased deposition of nitrogen from atmospheric sources because of fossil fuel combustion and forest burning. Both of these processes release a variety of solid forms of nitrogen through combustion.

Livestock ranching. Livestock release a large amounts of ammonia into the environment from their wastes. This nitrogen enters the soil system and then the hydrologic system through leaching, groundwater flow, and runoff.

Sewage waste and septic tank leaching.

Source:

Pidwirny, M. (2006). "The Nitrogen Cycle". Fundamentals of Physical Geography, 2nd Edition. Date Viewed. http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/9s.html