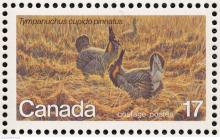

The prairie-chicken has lost as much as 84 percent of its historic prairie and grassland

The lesser prairie-chicken (Tympanuchus pallidicinctus) belongs to the grouse family of birds so iconic to prairie culture. This brown-barred, stocky species nests in shrubbery and grasses of the Texas panhandle, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Kansas and Colorado. David Hunter, owner of Hunter’s Livestock Supply in Woodward, recollected that the prairie-chickens were often spotted on his family’s 120-year-old farm in eastern Woodward when he was young. “There were just thousands of them everywhere,” the 57-year-old told me.