America’s agricultural landscape is now 48 times more toxic to honeybees, and likely other insects, than it was 25 years ago, almost entirely due to widespread use of so-called neonicotinoid pesticides, according to a new study published today in the journal PLOS One. This enormous rise in toxicity matches the sharp declines in bees, butterflies, and other pollinators as well as birds, says co-author Kendra Klein, senior staff scientist at Friends of the Earth US. “This is the second Silent Spring. Neonics are like a new DDT, except they are a thousand times more toxic to bees than DDT was,” Klein says in an interview.

Using a new tool that measures toxicity to honey bees, the length of time a pesticide remains toxic, and the amount used in a year, Klein and researchers from three other institutions determined that the new generation of pesticides has made agriculture far more toxic to insects. Honey bees are used as a proxy for all insects. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency does the same thing when requiring toxicity data for pesticide registration purposes, she explained.

The study found that neonics accounted for 92 percent of this increased toxicity. Neonics are not only incredibly toxic to honeybees, they can remain toxic for more than 1,000 days in the environment, said Klein. "It’s stunning. This study reveals the buildup of toxic neonics in the environment, which can explain why insect populations have declined,” says Steve Holmer of American Bird Conservancy.

As insects have declined, the numbers of insect-eating birds have plummeted in recent decades. There’s also been a widespread decline in nearly all bird species, Holmer said. “Every bird needs to eat insects at some point in their life cycle.”

Neonic insecticides, also known as neonicotinoids, are used on over 140 different agricultural crops in more than 120 countries. They attack the central nervous system of insects, causing overstimulation of their nerve cells, paralysis and death.They are systemic insecticides, which means plants absorb them and incorporate the toxin into all of their tissues: stems, leaves, pollen, nectar, sap. It also means neonics are in the plant 24/7, from seed to harvest, including dead leaves. Nearly all of neonic use in the U.S. is for coating seeds, including almost all corn and oilseed rape seed, the majority of soy and cotton seeds, and many yard plants from garden centers.

However only 5 percent of the toxin ends up the corn or soy plant; the rest ends up the soil and the environment. Neonics readily dissolve in water, meaning what’s used on the farm won’t stay on the farm. They’ve contaminated streams, ponds, and wetlands, studies have found.

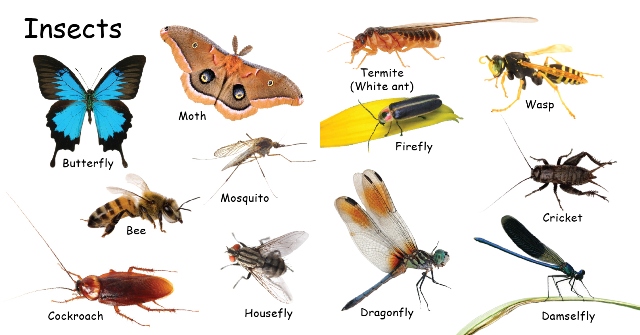

Some scientists have been warning that there is an “insect apocalypse” underway. A global analysis of 452 species in 2014 estimated that insect abundance had declined 45 percent over 40 years. In the U.S. the numbers of iconic Monarch butterflies has fallen 80 to 90 percent in the last 20 years. A study published last month reported that 81 species of butterflies in Ohio declined by an average of 33 percent in the last 20 years. Systematic measurements of butterfly populations are the best indicator of how the world’s 5.5 million insect species are doing, the authors of the Ohio study noted.

Not only do bees, butterflies, and other insects pollinate one-third of all food crops, declining insect numbers can also have catastrophic ecological repercussions. Renowned Harvard entomologist E.O. Wilson has said that without insects the rest of life, including humanity, “would mostly disappear from the land. And within a few months.”

In April 2019 a major study warned that 40 percent of all insect species face extinction due to pesticides—particularly neonics, since they’re the most widely used insecticide on the planet.

Source: National Geographic, 6 August 2019

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2019/08/insect-apocalyps…

- Login om te reageren