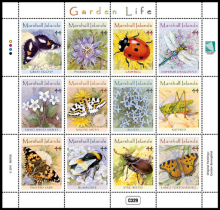

Our gardens become feeding stations for bees, butterflies, bats, hedgehogs, birds and other wildlife provided you don't use pesticides

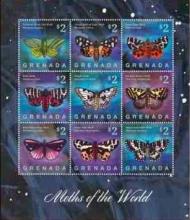

We grow flowers in our gardens for our own enjoyment. But colour and perfume are really the plants’ way of advertising themselves to insects. Sweet nectar and protein-rich pollen are bait to encourage insects to visit. In return, pollen is carried from one flower to another on their bodies so the flowers are fertilised. Bees are among the most beneficial insects for a garden. The best way to attract them to your garden is to provide them with some of their favourite plants such as lavender, foxgloves, rosemary, sunflowers and bluebells. Flowers with long narrow petal tubes, such as evening primrose and honeysuckle, are visited by moths and butterflies. Only their long tongues can reach deep down to the hidden nectar. Short-tongued insects include many families of flies and some moths. They can only reach nectar in flowers with short florets. Hoverflies, wasps, ladybirds, lacewings, ground beetles and centipedes are the gardener’s friends and will help control garden pests such as aphids and caterpillars. Insects such as spiders, mites, millipedes, sow bugs, ants, springtails and beetles inhabit the soil food web in the uppermost 2 to 8 inches of soil. They participate in decomposing plant and animal residue, cycling nutrients, creating soil structure and controlling the populations of other soil organisms, including harmful crop pests. Decaying organic matter in soil is the source of energy and nutrients for garden vegetables and ornamental plants. By growing flowers attractive to a range of insects, our gardens can also become important feeding stations for bats, hedgehogs, birds and other wildlife. The most important factor when encouraging wildlife into your garden is not to use insecticides.